Cuban tattoo artists battle bureaucracy

and censorship.

By Jessica Weiss

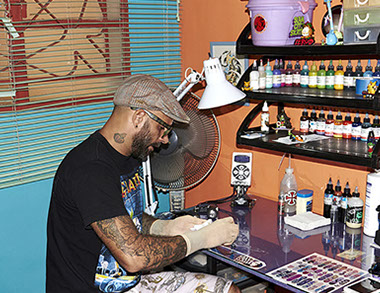

Rioger Martinez Navarro perches on a black chair, poised before his friend’s outstretched left forearm. Tables full of ink and machines clutter the front of this one-floor Havana apartment-turned-tattoo studio. In the kitchen, the apartment’s owner, a blind, middle-aged woman, clanks pots and pans as she makes coffee.

Photo by Jessica Weiss

After studying drawing and painting in college, 24-year-old Rioger Martinez Navarro now tattoos full-time out of his Old Havana studio.

A half-dozen bystanders hover around, including Martinez’s dad. But the artist is quiet and concentrated, disconnected from the noise and chatter. He slides on headphones, pumping out heavy electronic bass.

With a marker, the 24-year-old with a thin red mustache draws a rough sketch of an elephant down the length of his customer’s left arm and then leans back to size it up. Satisfied, he snaps on a pair of latex gloves, opens a fresh needle, and positions the electric tool. As the machine buzzes, the first shades of ink appear. The client, a 33-year-old DJ, takes a deep breath as the skin of his arm is pricked and transformed. The distinct sound of a tattoo session is the same anywhere in the world.

But Martinez’s studio is unmarked, hidden in a nondescript house on a small side street in Old Havana. For tattoo artists in the Cuban capital, it’s far safer to work underground.

“Many things remain under government purview in Cuba,” says Ted Henken, a professor at Baruch College in New York and author of Entrepreneurial Cuba: The Changing Policy Landscape. “Whenever officials feel threatened, they can always crack down and say, ‘We’re in control — don’t get too creative.’ ”

Starting a tattoo business is a serious challenge on the communist island, where the profession has long existed in a legal gray area. Basic supplies, from ink to needles to tattoo guns, have to be smuggled through the black market or rigged from random spare parts. Training happens in backrooms and through word of mouth. And artists like Martinez live in the constant shadow of random state crackdowns. Last May, inspectors raided tattoo shops across Havana and confiscated guns, needles, and ink, forcing dozens of artists to scale back or close completely.

Photos by Jessica Weiss

Yet business has never been better in La Habana. Everyone from skaters to politicians to police shows off inked skin, from small stamps to full sleeves, crafted by scores of professionals who have caught the eye of the international media and even reality shows such as Ink Master. “This is my form of expression,” says Martinez, whose own arms and chest are covered in tattoos. “This is my art.”

Tattoo artists work at a unique nexus in the new Cuba, where the economy is rapidly changing as President Barack Obama makes a historic visit. They’re both small-business operators and artists, entrepreneurs and rebels against a totalitarian system. How the Castro regime decides to deal with people like Martinez will tell the world much about how Cuba will change as a nation.

The artists themselves are split over how they should fit in. Some argue it’s time they were fully regulated by the state and considered small-business owners, a thriving group that has expanded under loosened rules to fill trades from running shops to driving taxis.

But others, such as Martinez, consider tattooing an art form and want it officially recognized alongside other revered expressions such as painting and sculpting.

“I’m not a businessperson,” Martinez says. “This has to do with culture. I’m here doing what I can and giving people something they want, and I’m doing a good, safe job. Why should I live in the shadows for it?”

Life wasn’t easy in Cuba in the early 1990s. In the wake of the Soviet Union’s implosion, the Castro-run economy tanked, sparking shortages in everything from food to clothing. At the time, Che Alejandro Pando Napoles was a surfer and skater in his early 20s, scraping a living as a carpenter and gardener. He was eager for something more.

That’s when some of his friends around town began to experiment with tattooing. There was Evelio in Cerro, and Leo and Hans in Alamar, who all got hooked on the curious body art. Pando had always loved to draw, so he gave it a try with ink and needles on himself.

“Everything was done by hand with pens and sewing needles and thread and Chinese ink,” he says. “It was a disaster, just trying to figure out a way to make a machine, like with a Walkman motor and sewing needles attached with thread.”

Cubans have long been masters of invention as decades of deprivation have created an impressive DIY culture. The rise of tattooing on the island is a vivid illustration of that talent, as a scene that began with jerry-rigged machines has evolved to produce first-class work. That unique Cuban style has grown far beyond one-star flags and Che Guevara’s mug.

For decades, though, tattooing meant one thing on the island: that you had done prison time. Through the ’70s and early ’80s, ink on the skin was a sure sign of a stint behind bars. In fact, when Fidel sent 125,000 Cubans to Miami during the 1980 Mariel Boatlift, tattoos finally tipped off authorities that Castro was emptying his jails into Florida. Customs officials learned that Cuban criminals sported specific tats depending upon their specialty: three diverging lines meant a drug dealer; an inverted leaning cross was a weapons supplier; a heart with wings meant an executioner.

Photo by Allison Dinner

Jose tattoos a customer at his shop in Sancti Spíritus, a town in central Cuba.

But by the end of the ’80s, attitudes toward tattoos began to change. Although glimpses of pop culture outside the country were sparse, they revealed a global Zeitgeist where tattoos were hip. Skin ink’s reputation softened as greater numbers of tattooed tourists arrived, and increased air travel to the island meant artists could smuggle in better supplies and reference materials such as books and magazines.

The scene really began to coalesce in the early ’90s, when Pando and his friends started tattooing just as a tightening U.S. embargo and loss of Russian support made it difficult to even find food. The early experiments weren’t all successful.

“We all have blotchy patches of ink on our arms,” he says, “because we tried to tattoo ourselves before we found any customers.”

They started learning at an intriguing time for artists on the island. In the early ’90s, Fidel began creating special exemptions allowing creatives to sell their work abroad.

The handful of incipient tattooists considered themselves artists of a new category, a fusion of underground movements such as piercing, rap, and rock music with more traditional art forms like pottery and sculpture. According to Pando, the first to be lured to tattoos were those who, in some way, felt marginalized from more contemporary forms of art and expression.

“People wanted to go against the system,” he says. “But they were also rebelling against the false idea that this tattoo, this mark, meant a total rejection of society.”

In 1996, bar owner María Gattorno, known as the “Holy Mary of Heavy Metal,” organized the first meeting of tattoo artists in her downtown Havana bar, Maria’s Patio. Officially called La Casa Comunal de la Cultura Roberto Branly, the space transformed into the de facto meeting place for young Cubans who felt misunderstood. The patio hosted debates on vampirism, cyberpunk, and sex.

As tattooing grew more popular, the government never explicitly banned it, but it clearly didn’t agree with the trend. Autoclaves, which are essentially pressure cookers used for equipment sterilization, were outlawed. Their use was made punishable by jail time.

Photo by Allison Dinner

Havana skateboarder Yojani shows off new ink on his arm.

In December 1997, tattoo artists Hans León, Leo Canosa, and Iosvany Grave de Peralta rented an apartment in Guanábo Beach and opened a tattoo studio. Through images they had seen in tattoo magazines, they acquired all the supplies needed to run a professional shop. But on the second day of business, police arrested León and Grave de Peralta, confiscated all of their equipment, and slapped them with hefty fines.

The two weren’t discouraged, though. When he got out of jail, León became a dedicated advocate for Havana’s handful of up-and-coming inkmasters. He thought they needed to fight for their legitimacy and inclusion alongside other art forms instead of living as outcasts. With the support of other artists, especially Canosa, León succeeded in getting tattooing its own project in the Asociación Hermanos Saíz, a group for young artists. The name of their project was Lienzos Vivientes, or “living canvases.” That, he says, suggested a tattoo as a piece of art that works with the body, “not just a mark of ink.”

“That’s when I began my own revolution,” León says. “I began to host events and ensure that all the tattoo artists were using the proper safety measures and hygiene standards.”

Over the next two years, he organized four shows bringing together tattoo artists, rappers, hip-hop artists, DJs, and other visual artists such as sculptors. He held a conference at the University of Havana, as well as activities and meetings in the community.

“That is how you show the society your art,” he says. “You can’t be against the government. You have to use all your resources to make the government recognize you as an institution and an artist.”

It seemed to be working, at least on the surface. There was a sense of growing acceptance for tattoos and the need for organization. In the project’s second year, León and Canosa created a certificate to distinguish tattoo artists who worked in exceptional and sanitary conditions, and awarded Pando and seven others.

But in 2000, León got married and moved to Canada with his wife. Havana’s tattoo scene lost its strongest advocate, and other well-known tattoo artists also began fleeing. Still, Pando watched with fascination as the previously taboo art form became ever more popular with young Cubans.

“People in Cuba want to belong to this world,” Pando says. “And they want something that makes them unique.”

As the machine buzzes, tracing the lines of an elephant body, Martinez is natural and calm. After so many years of traditional artistic training, of getting his hands dirty on paper and canvas, he says a tattoo gun is now his preferred medium.

“Now I sit down to draw something on paper, and it doesn’t come out as well as when I do it on the skin,” he says. “The skin is my best canvas. And every skin is different.”

The personal stories of Martinez and other tattoo artists in Havana both echo the rise of tattooing in Cuba over the past two decades and underscore the challenges that artists and entrepreneurs face in a changing country. As the embargo begins to ease, many are watching eagerly to see if the Cuban government adopts a more lenient attitude toward both creative pursuits and small businesses.

Art has always played an outsize role in Cuba. With a delirious hybrid of Spanish, Caribbean, and African styles, a unique visual arts scene has grown on the island. In recent years, the contemporary scene has boomed internationally, especially after the government in the ’90s carved out an exemption for artists that allows them to travel freely in and out of the country. Today work by many contemporary Cuban artists can be found in some of the world’s most famous museums and galleries.

Born in 1991 in Havana, Martinez had artistic dreams to match those successes. As a kid, he was always drawing. He studied at Havana’s prestigious Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro, where he specialized in drawing and painting. Upon graduation, he was handed an “artist ID” card to signify his position as an independent artist, allowing him to practice forms such as painting, ceramics, and photography.

His plan, always, was to paint. And he did, in earnest. He sought out galleries to show and sell his work. On the canvas, his expressions were free-flowing and unexpected — a way to “embody and express images and experiences that are archived in my subconscious,” he says, “uprooting my ego and connecting me more with myself.”

Photo by Allison Dinner

Longtime skateboarder Che Alejandro Pando Napoles, who goes by Che, was one of the first tattoo artists in Cuba. He got his start in the '90s.

But the life proved challenging. Galleries tended to display works by the same few painters over and over, and those painters were often distinguished members of society, such as the sons and daughters of political figures and celebrities, he says.

After three years, he decided to try something new. Tattooing wasn’t in the Cuban Official Gazette (which publishes the Labor Code and legal safeguards for employees and employers), and Martinez didn’t hold tattoos in a high artistic opinion. But he was curious and broke, so he tattooed a friend to earn a few bucks.

Supplies are easier to come by today than they were in the early ’90s, but they’re still scarce. Artists who don’t have American-based friends and family to deliver equipment must buy it on the black market at a huge markup. Prices for ink and needles can go for three or four times the cost in the States.

When he started, Martinez didn’t even know that individually wrapped, sterilized needles existed. After poking his friend’s skin unsuccessfully, Martinez experimented with making his first machine.

“It looked like an atomic bomb,” he laughs. “The pedal was made of wood, there were cables coming out everywhere, but it worked and went through the skin.”

His early tattoos were disastrous, he says, but he improved with each one, earning a few bucks here and there. It took him six months — and lots of bravery from his friends — to get the technical part down. “The atrocities I committed on my friends’ skin were horrible,” he laughs. “They were really generous. But I was hooked. I loved it.”

Photo by Allison Dinner

Che uses skateboards as shelves in his studio in Cerro, Havana.

Martinez soon found a booming community of young, ambitious tattoo artists ready to create a new scene on the island.

Some, such as 32-year-old Ana Lyem Lara González, even abandoned more stable careers for the dubiously legal profession. González had been working for six years as an architect before she began getting tattoos from a friend in Havana. She was drawn to his focus on detail and the creative exchange between herself and the artist, so she asked to begin training with him. “And immediately I became obsessed,” she says. “I loved it.”

She did her first tattoo on pork skin. Then on friends, for free. The first time she practiced on a fellow tattoo artist, he gave her feedback in real time. “He kept saying to me: ‘Put the needle in deeper — you’re not doing anything,’ ” she laughs.

Two and a half years ago, she quit her job to tattoo full-time. “Everyone said I was crazy, because it was a really good job,” she says, “but I knew I wanted to live off this.”

Others, like Juan Antonio, who is 37, came from an art background. As a kid, Antonio had loved painting. Seven years ago, he was working as an illustrator when he began to study tattooing simply by observing a friend. In the beginning, he practiced only on himself, experimenting with different inks and machines. Because he holds dual Spanish citizenship, he went to Spain to buy materials and study from Spanish pros. Now he tattoos five days a week from his living room.

And 33-year-old Yusep Saqués followed in the footsteps of his older brother, a well-known Havana tattoo artist. They grew up in an artistic family — Saqués’ grandfather was a tailor from Spain, his uncle was a cartoonist, and his father a painter. Saqués studied ceramics but entered the field of social work. He began learning tattooing from his brother in the early 2000s while working odd jobs. Then, in 2009, he decided to become a full-time tattoo artist.

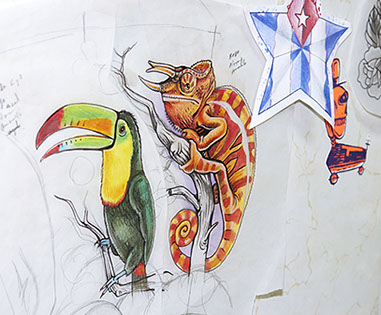

Photo by Allison Dinner

Che's cartoon work.

For each of them, tattooing was un embullo — a passion that felt exciting and right. But it also offered a chance to make real money.

“A good tattoo artist gets paid cash, pays no taxes on income, and can make the equivalent of $300 per week,” says Allison Dinner, a photographer who has been documenting tattoo culture in Cuba for the past two years. “To put that into perspective: A typical government worker makes about $25 a month.”

But that money is being made outside the government’s narrow window for those not working for the state. In 2010, the Castros expanded the designation of cuentapropistas, or small-business owners. Since then, the sector has grown from less than 150,000 licensed operators to more than half a million. Cuentapropistas include knife sharpeners, palm tree trimmers, and button upholsterers — but not tattoo artists.

“I always say there’s been significant change under Raúl, but it hasn’t been sufficient,” Henken, the professor and author, says. “So far, it hasn’t produced the vibrant, innovative, modern kinds of businesses many people had hoped for.”

Yet the city’s best tattoo artists show all the trappings of full-fledged businesses. Their shops are clean and organized. Many distribute flyers and have business cards. Assistants take phone calls and organize schedules. Though most tattoo “shops” are artists’ living rooms or bedrooms, some artists rent spaces outside the home.

Martinez also has a Facebook page, Rioger Tattoo, where he posts photos and videos of his clients and creations, which helps attract customers from all over the world. Last year, he was interviewed by International Ink magazine. He has sought out training in sterilization techniques and is looking for opportunities outside the country to continue to market his art.

He’s even been thinking about placing a sign outside the front door to advertise his art gallery and tattoo business.

But that, he says, might be taking it a bit too far. “For now, I’m still underground.”

Photo by Allison Dinner

Sketches and drawings of tattoos in every style and subject line the walls at an Old Havana studio.

Pando wasn’t entirely surprised by the knock. It came last May as he worked in his home studio on a tree-lined street in Cerro, in a hilly section of west Havana. The space is filled with paraphernalia from his alternative life; some of his old skateboards and surf gear adorn the orange and blue walls. He even uses skateboards as makeshift shelves. Posters and tattoo designs surround the space around the black chair where his clients sit.

When his assistant opened the door that day, four people were standing in the street. The two women had tattoos and were acting like clients. But something was off. “They were acting weird and changing their story,” Pando says. “Something was not right.”

He had a feeling in his stomach; in prior weeks, he’d heard from other tattoo artists that inspectors had been showing up randomly and confiscating equipment or forcing the shops to close. Some of the artists had been tricked into giving tattoos to inspectors who revealed themselves only when it was time to pay.

Now, he knew, they had come for him.

The recent crackdown illustrates both the tenuous ground that Cuban tattoo artists occupy and the many questions surrounding reforms on the island. Even though the government has created a semi-independent private sector, no one is free from the Castros’ whims. And artists who push the envelope have faced their own harsh pushback.

“This is a huge problem,” Hans León says. “The government not only controls the way people make money or run private businesses; it refuses to put tattooing in the constitution as something illegal, but it’s also not recognizing it as art.”

Even as cuentapropistas have been given more freedoms, the government has randomly slammed its fist down on those who stretch too far. A few years ago, for instance, inspectors shut down a spate of home movie theaters that had begun showing 3D films. The homeowners had licenses to “operate equipment for children’s entertainment,” but movies were a step too far, apparently.

When it comes to tattoos, the situation is even more precarious. No one knows exactly why the government chose last May to crack down, but there are rumors. Some say it was sparked by a health scare, maybe even a case of AIDS, from unsterilized equipment. Others say a new censorship push was to blame.

Either way, few if any of the artists faced jail time. Pando got off with a bribe. He paid $50 per inspector — for a total of $200 — for them to leave his equipment. But many other artists lost invaluable gear. Even Pando decided to shut down the studio for three months. Tattoo artists across the city did the same — some for just a few days, others for months. Some only tattooed friends or at night in new clandestine spaces.

In that moment of uncertainty, Pando became somewhat of an unofficial leader of the artists. He approached attorneys to seek legal counsel. He went to the Ministry of Labor, where no one was willing to give any kind of explanation, except that tattooing was an illegal practice and that there was no government license for it.

Photo by Allison Dinner

Teresa mixes colors at her shop in Havana.

“The truth is we have no idea why it happened then,” Pando says, “and we probably never will.”

The tattoo artists began gathering to work on solving the problem, but after their second meeting, they were warned that any future meetings could lead to their being accused of counterrevolutionary activities. Many decided to abandon the fight and simply wait it out. Most have since reopened but remain firmly in the shadows.

The situation remains murky. Why not simply regulate tattoo parlors like other cuentapropistas? The resistance might speak to the simple reality that tattoos — like other unconventional art forms — are still shunned by authorities.

“Whereas we’ve turned the page in the U.S. on tattoos and they’re hip, in Cuba they’re hip, but there’s a certain rejection of it,” Henken says, “like they’re not sanitary or a sign of low class. And I think the combo of it being out of the legal framework and something that has a certain pejorative connotation to it means they’ll continue on the margins.”

But that attitude comes at a cost, Pando says. As more people set up studios, including those with no clue what they’re doing, public health becomes increasingly threatened.

Indeed, many shops are little more than dirty shacks where $5 tattoos are given with no apparent sterilization. On one side street in central Havana, a black sign advertises “Tattoos” amid a row of potted plants on a second-floor balcony. Up a narrow flight of stairs, the “studio” is a cramped living room where a tattoo gun sits on a desk. A family eats lunch nearby. “Would you like a tattoo?” someone asks.

Pando and other artists say the government’s continued denial to license their practice only further deteriorates tattooing’s image — and places people’s health at risk.

But treating tattoo businesses as art studios comes with its own perils too. Even as it embraces a tighter U.S. relationship, the Castro regime has still cracked down on artists who push boundaries too far.

During the Havana Biennial last June, installation and performance artist Tania Bruguera planned a piece titled Tatlin’s Whisper #6, which involved setting up a microphone and inviting anyone to speak uncensored for one minute. She planned to perform the piece in Revolution Plaza. But as soon as she announced her project, police took her into custody on charges of disrupting public order. The authorities confiscated her Cuban passport and threatened to bring her to trial.

Another bold artist faced an even more harrowing ordeal. Danilo Maldonado Machado, a 32-year-old better known as El Sexto, has repeatedly created graffiti works that tweak the regime. “I needed to do it,” he says. “The moment I decided to be an artist, I finally felt free.”

Last year, after spraying “Fidel” and “Raúl” on a pair of live pigs, he was incarcerated without trial in Cuba’s Valle Grande prison for ten months. Now free again, he’s continued to criticize the government, including by using his body as a canvas. He has tattooed prominent dissident figures on his skin, which he says makes these people impossible to erase. “Their souls remain alive.”

“How far can a government go to control you?” he asks, referring to a tattoo. “All the way to your blood and your bones and your skin? I don’t think so.”

Beyond a beautiful wood-and-stained-glass door in a colonial-style building in Old Havana, a new type of art space thrives in Havana. It’s not full of expensive, gallery-style framed art. This is an edgy space, filled with the energy of up-and-coming young artists bursting with ideas, both avant-garde and expressive. This week, a display of decorated skateboards adorns the walls around the entrance. On another portion of the walls, kids were allowed to go crazy with pencils and markers. On another, a small sticker shows a cartoon Cuban flag with a knife through it.

A spiral staircase leads upstairs to the tattoo parlor, a spotless and modern room. The walls hold photos of finished tattoos, sketches, and shelves with thick volumes of drawings of tattoos in every style and subject — lizards, dragons, tribal symbols, flowers.

Last year, Leo Canosa opened La Marca, the country’s first professional tattoo shop, as an art studio. The ground floor is a sort of cultural space and meeting center, and tattooing takes place upstairs.

La Marca is a glimpse of the possibilities of tattooing in a new Cuba, where it respectfully and dutifully toes the line between art and business — where customers know they’ll get high-quality and safe work, but where they’re also allowed to express themselves fully.

“We define ourselves as a cultural center, where anyone can come, even kids and teens,” says Ailed Duarte, the shop’s owner and Canosa’s wife. “We want to expand the arts, and we want to improve the image of the tattoo in Cuban society.”

This gallery/studio has had no legal troubles and faced no official sanctions — it was even an exhibition space at the Biennial, where a renowned Mexican artist tattooed guests in the gallery. Last year, Canosa also appeared on Mesa Redonda, a government-sanctioned news and discussion program, to promote his shop.

But La Marca’s success doesn’t necessarily pave the way for others. Though clampdowns on Havana’s studios have stopped, the fear persists.

Photo by Allison Dinner

La Marca is the country’s first professional tattoo shop, opened last year as an art studio in Old Havana.

Despite the challenges, the number of tattoo artists has steadily grown, both in Havana and in cities throughout the island. There are still one or two tattoo conventions a year, which bring together a handful of artists looking to acquire new skills or inspiration. Recently, Canosa held a sterilization workshop at La Marca.

Dinner, the photographer, says you can now go to any city across the country and find at least one tattoo artist.

“I knew I’d find someone in Havana, but I was so surprised by the talent in other cities,” she says. “In Sancti Spíritus, smack dab in the middle of the country, I saw one of the most talented artists I’ve seen so far. The fact that he’s so isolated makes it even more incredible.”

For Pando, who remembers when only a handful of tattoo artists worked in backrooms, it’s surreal to reflect on how much the art has grown and how mainstream it has become. Now in his 40s, he works out of a studio space in his house, in Cerro, with two other artists and an assistant. Though he tattoos a range of styles, from classic American tattoos to 3D images, his favorites are funny cartoons. In 2010, he went to Spain for a tattoo convention. He makes good money, especially compared to his days as a gardener and carpenter rigging skateboards in the ’80s.

“It’s a well-paying job, and you have the liberty to do whatever you want,” he says. It’s not uncommon for a 15-year-old to come into his shop with a parent, seeking a tattoo for the teen’s birthday. And not only that, he says, but people from the government — police, judges — also stop in to get inked. Where once there were ten quality artists, now he knows 50.

Martinez and others say they’ll continue pushing for official recognition as artists. Whether he gets it or not, he’ll keep tattooing. Business, after all, has never been better. “There’s a huge tattoo culture now,” he says. “I can easily do four a day, and I have to schedule people days in advance.”

Others will fight for a cuentapropista category for tattoo artists.

On his visit to the island, Obama discussed issues of freedom of expression and better access to business opportunities. But will the Castros listen?

The tattoo industry may be among the first to find out.

“The Revolution has created its own establishment, against which young, innovative, creative people will revolt,” Henken says. “So at some point, you have to ask: What does it mean to be a revolutionary in a revolutionary society?”

Photography by

Allison Dinner and Jessica Weiss

Art direction and design by

Miche Ratto

Source videos via Shutterstock